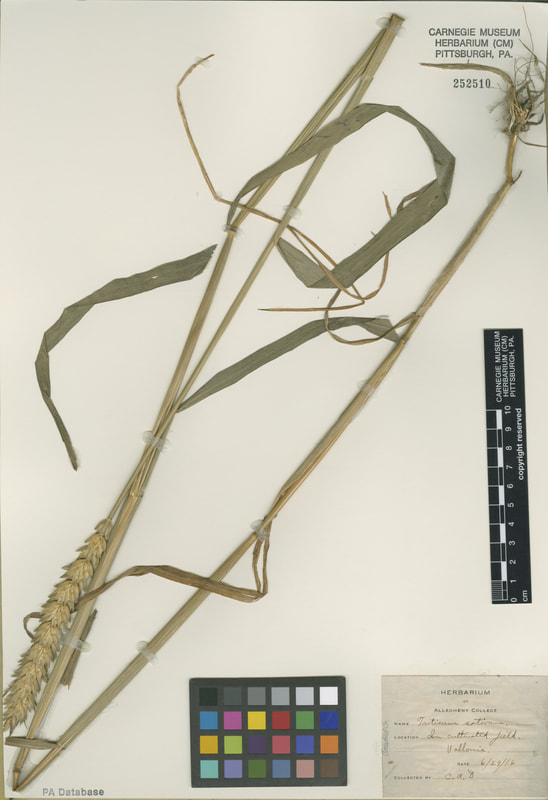

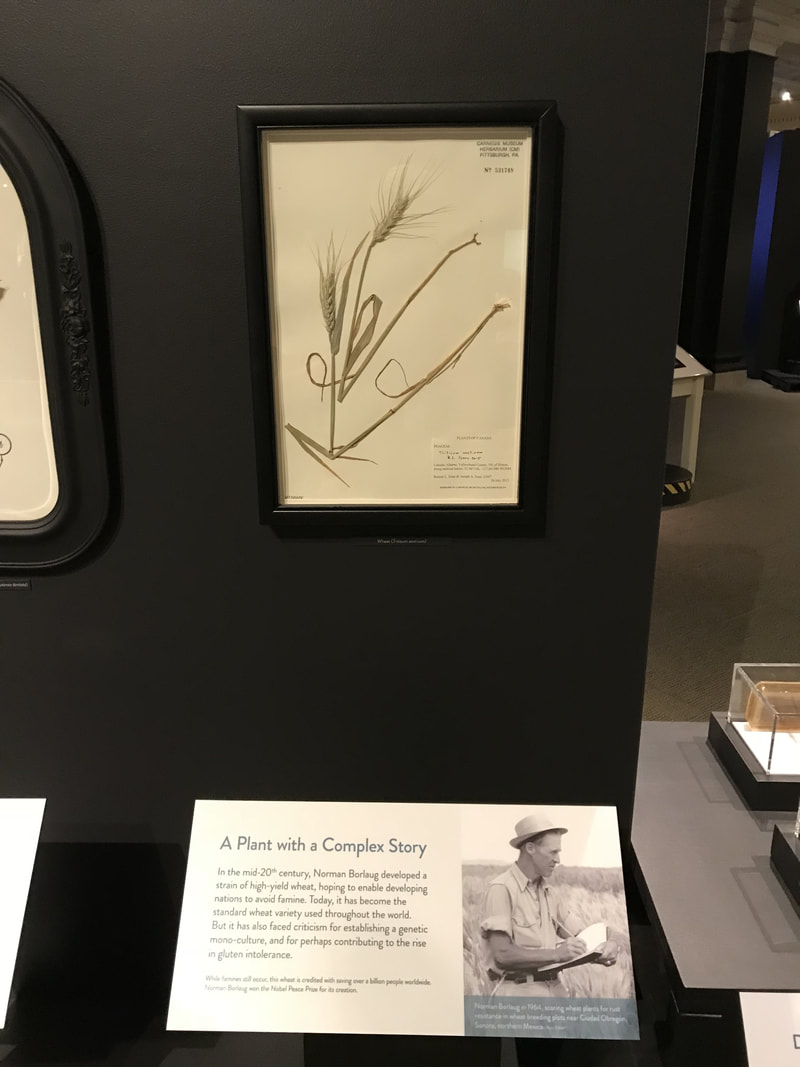

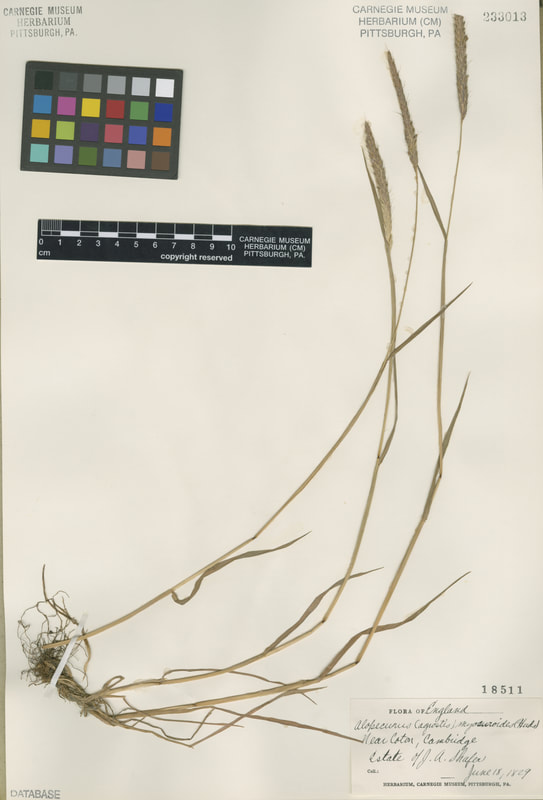

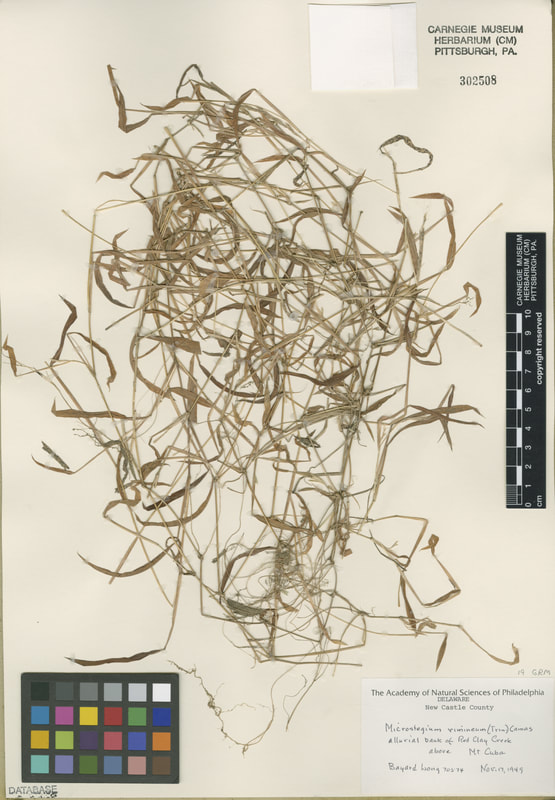

Collected on this day...

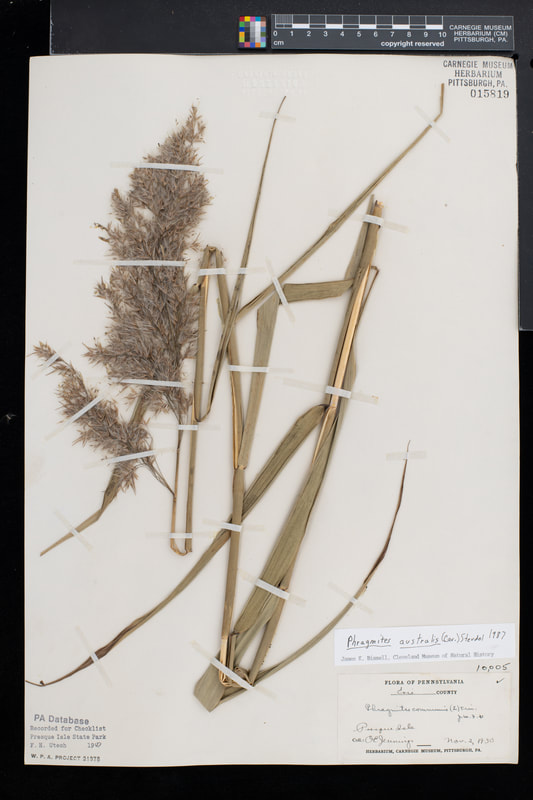

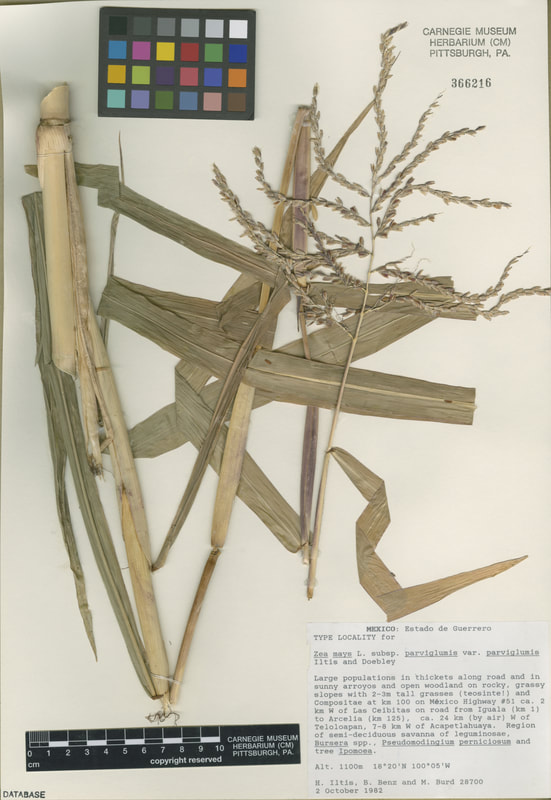

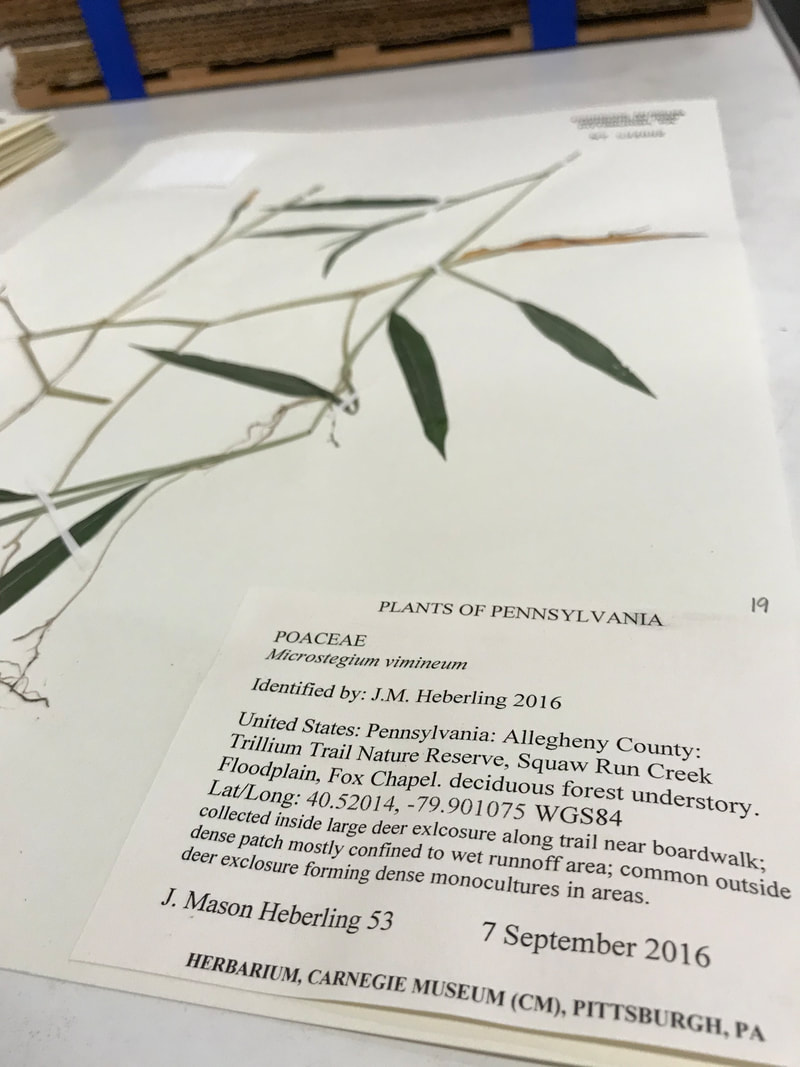

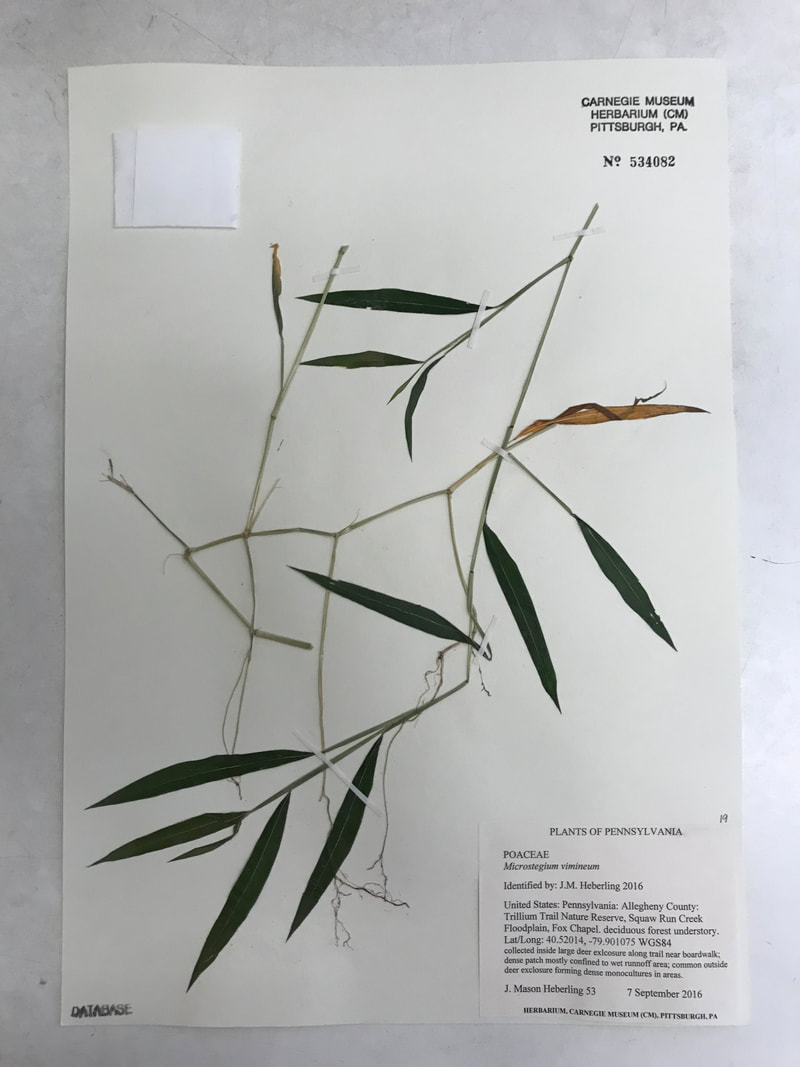

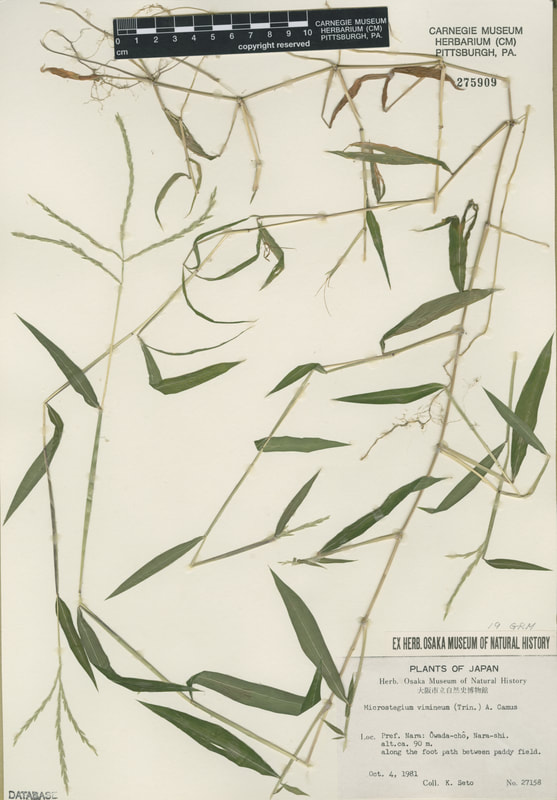

a weekly blog featuring specimens in the Carnegie Museum herbarium.

Each specimen has an important scientific and cultural story to tell.

Each specimen has an important scientific and cultural story to tell.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation grant no. DBI 1612079 (2017-2019) and DBI 1801022 (2019-2022). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed